Recently, I attended the annual advisory council meeting for an NSF-funded Ethical & Responsible Research (ER2) project focused on Registered Reports, led by Amanda Montoya and William Krenzer. The project seeks to facilitate uptake of Registered Reports among Early Career Researchers by understanding individual, relational, and institutional barriers to doing so. The first paper from the project has now been published (Montoya et al., 2021), with several more exciting ones on the way. This post is inspired by our conversations during the meeting, and thus I do not lay sole claim to the ideas presented here.

A quick primer on Registered Reports before getting to the point of this post (skip to the next paragraph if you are a know it all): Traditional[1] papers involve the process we are all familiar with, in which a research team develops an idea, conducts the study, analyzes the data, writes up the report, and then submits it for publication. We how have plenty of evidence that this process has not served our science well, as it created a system in which publication decisions are based on the nature of the findings of the study, which has led to widespread problems of p-hacking, HARKing, and publication bias (Munafò et al., 2017). Registered Reports are an intervention to the problems created through the traditional publication process (see Chambers & Tzavella, 2021, for a detailed review). Rather than journals reviewing only the completed study, with the results in hand, Registered Reports break up the publication process into two stages. In Stage 1, researchers submit the Introduction, Method, and Planned Analysis sections—before the data have been collected and/or analyzed. This Stage 1 manuscript is reviewed just as other manuscript submissions are, with the ultimate positive outcome being an In-principle acceptance (IPA). The IPA is a commitment by the journal to publish the manuscript regardless of the results, so long as the authors follow the approved protocol and do so competently. Following the IPA, the researchers conduct the study, analyze the data, and prepare a complete paper, called the Stage 2 manuscript, and resubmit that to the journal for review to ensure adherence to the registered plan and high-quality execution. Whereas publication decisions for traditional articles are made based on the nature of the results, with Registered Reports publication decisions are based on the quality of the conceptualization and study design. This change removes the incentive for researchers to p-hack their results or file-drawer their papers (or for editors and reviewers to encourage such), as publication is not dependent on plunging below the magical p-value of .05. In my opinion, Registered Reports are the single most important and effective reform that journals can implement. So, naturally, it is the reform to which we see the greatest opposition within the scientific community[2].

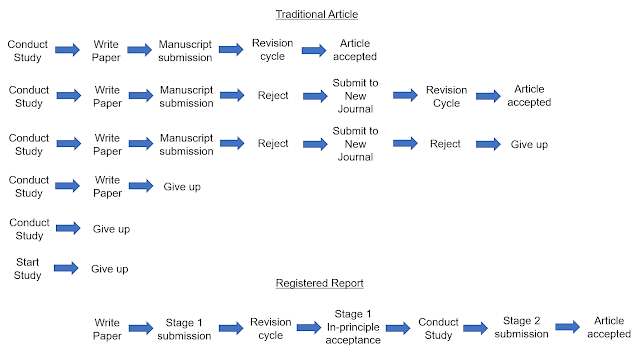

A recurring topic of conversation at our meeting was about the review time for Registered Reports, and how it compares to publishing traditional papers. Traditional papers have a single review process, whereas with Registered Reports the review process is broken up into two stages. Thus, on first glance it seems obvious that Registered Reports would take longer to conduct because they include two stages of review rather than one, and thus it is no surprise that this is a major concern among researchers.

But is this true? As Amanda stated at our meeting, it is hard to know what the right counterfactual is. That is, the sequence and timing of events for Registered Reports are quite clear and structured, but what are the sequence and timing of events for traditional papers? Until she said that, I hadn’t quite thought about the issue in that way, but then I started thinking about it a lot and came to the conclusion that most people almost certainly have the wrong counterfactual in mind when thinking about Registered Reports.

Based on my conversations and observations, it seems that

most people’s counterfactual resembles what is depicted in Figure 1. Their

starting point for comparison is the point of initial manuscript submission. In

my experience as an Editor, the review time for a Stage 1 submission, and the

number and difficulty of revisions until the paper is issued an in-principle

acceptance (IPA), is roughly equivalent to how long it takes for traditional

papers to be accepted for publication.[3]

Under this comparison, Registered Reports clearly take much longer to publish

because following the IPA, researchers must still conduct the study and submit

the Stage 2 for another round of (typically quicker) review, whereas the

traditional article would have been put to bed.

Figure 1. A commonly believed, but totally wrong, comparison between Registered Reports and traditional articles.

I have no data, but I am convinced that this is what most people are thinking when making the comparison, and it is astonishing because it is so incredibly wrong. Counting time from the point of submission makes no sense, because in one situation the study is completed and in the other it has not yet even begun. To specify the proper counterfactual, we need to account for all of the time that went into conducting and writing up the traditional paper, as well as the time it takes to actually get a journal to accept the paper for publication. And, oh boy, once we start doing that, things don’t look so good for the traditional papers.

In fact, that phase of the process is such a mess and is so variable, it is really not possible to know how much time to allocate. Sure, we could come up with some general estimates, but consider the following:

It is not uncommon to have to submit a manuscript to multiple journals before it is accepted for publication. This is often referred to as “shopping around” the manuscript until it “finds a home.” I know some labs will always start with what they perceive to be the “top-tier” journal in their field and then “work their way down” the prestige hierarchy. In my group we always try to target papers well on initial submission, and just looking at my own papers about a quarter were rejected from at least one journal prior to being accepted. This should all sound very familiar to all researchers, and it is just plain misery.

It is not uncommon for manuscripts to be submitted, rejected, and then go nowhere at all. This problem is well known, as part of the file-drawer problem, where for a variety of reasons completed research never makes it to publication. Sometimes this follows the preceding process, where researchers send their paper to multiple journals, get rejected from all of them, and then give up. I had a paper that received a revise and resubmit at the first journal we submitted it to, but then it was ultimately rejected following the revision. We submitted to another journal, got another revise and resubmit, and then another rejection. This was, of course, extremely frustrating, and so I gave up on the paper. Many years later, one of my co-authors fired us up to submit it to a new journal, and it was accepted…..14 years after I first started working on it. That paper just as easily could have ended up in the file drawer.[4]

It is not uncommon for great research ideas to go nowhere at all. Ideas! We all have great ideas! I get excited about new ideas and new projects all the time. We start new projects all the time. We finish those projects….rarely. I estimate that we have published on less than a third of the projects we have ever started, which includes not only those that stalled out at the conceptualization and/or pilot phase, but also those for which we collected data, completed some data analysis, and maybe even drafted the paper. For some of these, we invested a huge amount of time and resources, but just could not finish them off. Things happen, life happens, priorities change, motivations wane. So it goes.

All of the above is perfectly normal and understandable within the normative context of conducting science that we have created. Accordingly, all of it needs to be considered in any discussion of comparing the timeliness of Registered Reports and traditional papers. Registered Reports do not completely eliminate all of the above maddening situations, but they severely, severely reduce their likelihood of occurrence. Manuscripts are less likely to be shopped around, less likely to be file drawered, and if you get an IPA on your great idea, chances are high you will follow through. We need to acknowledge that the true comparison between the two is not what is depicted in Figure 1, but more like Figure 2, where the timeline for Registered Reports is relatively fixed and known, whereas the timeline for traditional papers is an unknown hot mess.

Figure 2. A more accurate comparison between Registered Reports and traditional articles. Note that the timelines are not quite to scale.

(Edit: a couple of people have commented that the above figure is biased/misleading, because Registered Reports can also be rejected following review, submitted to multiple journals, etc. Of course this is the case, and I indicated previously that Registered Reports do not solve all of these issues. But "shopping around" a Stage 1 manuscript is very different from doing so with a traditional article, where way more work has already been put in. Adding those additional possibilities (of which there are many for both types of articles) does not change the main point that people are making the wrong comparisons when thinking about time to publish the two formats, and that Registered Reports allow you to better control the timeline. See this related post from Dorothy Bishop.)

To be clear, I am not claiming that there are no limitations

or problems with Registered Reports. What I am trying to bring attention to is

the need to make appropriate comparisons when weighing Registered Reports

against traditional articles. Doing so requires us to recognize the true state

of affairs in our research and publishing process. The normative context of

conducting science that we have created is a deeply dysfunctional one, and

Registered Reports have the potential to bringing some order to the chaos.

[1] I

don’t know what to call these. “Traditional” seems to suggest some historical

importance. Scheel et al.

(2021) called them “standard reports,” which I do not like because they

most certainly should not be standard (even if they are). Chambers & Tzavella

(2021) used “regular articles,” which suffers from the same problem. Maybe

“unregistered reports” would fit the bill.

[2]

Over 300 journals have adopted Registered Reports, which sounds great until you

hear that there are at least 20,000 journals.

[3]

Here, I am making a within-Editor comparison: me handling Registered Reports

vs. me handling traditional articles. There are of course wide variations in

Editor and journal behavior that makes comparisons difficult.

[4]

The whole notion of the file drawer is antiquated in the era of preprint

servers, but the reality is that preprints are still vastly underused.

Very informative, but I think you figure is a little biased. Any RR can be rejected as well. So, you have multiple streams on a "traditional" paper, but suggest the flow of a RR is very smooth. Either eliminate the reject/submit elsewhere from the traditional paper, or add more the bottom, RR flow. Probably better to do the latter.

ReplyDeleteI am not usually keen on responding to anonymous comments, but someone else mentioned this on twitter, so I added some text under Figure 2 to address the issue.

Delete*your figure* sorry

ReplyDeleteInformative written, top;)

ReplyDelete"The distinction between Registered Reports and traditional articles is well-articulated. How might preprint servers complement Registered Reports in addressing the file-drawer problem?"

ReplyDeleteDust Collector in Delhi

Centrifugal Blower in delhi

"Your point about the dysfunctional research ecosystem is compelling. Could funding agencies incentivize Registered Reports to reduce barriers?"

ReplyDeletepulse jet bag filter India

Centrifugal Blower in Manufacturer

"The anecdote about the 14-year publication timeline is striking. How can we better document these delays to advocate for systemic change?"

ReplyDeleteWet Scrubber Manufacturer

Pulse Jet Bag filter

"Registered Reports seem promising for reducing p-hacking. Do they also mitigate issues like incomplete data or ethical concerns during study execution?"

ReplyDeleteEvaporative Cooler Manufacturer

structural-steel-tubes distributors in bhubaneshwar

"The comparison figures are helpful. Have you considered adding quantitative data to strengthen the argument?"

ReplyDeleteCentralized Dust collector in dElhi

Checkered sheet dealer in gwalior

This blog offers great insights into effective online learning for young students. I’ve personally found that pyp online courses with one-on-one guidance really help in building strong conceptual understanding. Truly a great option for parents looking for structured PYP support!

ReplyDelete